Artchaeologies

How can Archaeology, whose etymology literally means “science of origins” and which is currently defined as exact science, can induce the creative act?

We have engaged with Elsa Mazeau, artist and myself, archaeologist, an experiment at the Pierre Emmanuel College in Pau, resulting from a collaborative work with the students to study the temporality and spatial organization of the Pierre Emmanuel high School.

This work allows us to approach with the students an appropriation of this newly built school, but also the restitution of their perception.

The specificity of this site poses constraints that will impose adapted approaches from the perspective of an ethnographic and multidisciplinary approach. Indeed, the building is recent, and built on the former Jean-Monnet College in the Zaragoza district, closed in 2012. It is therefore a new entity, without traces of ancient occupation, and cannot therefore be studied as an ancient site whose occupations are identified as the excavation progresses.

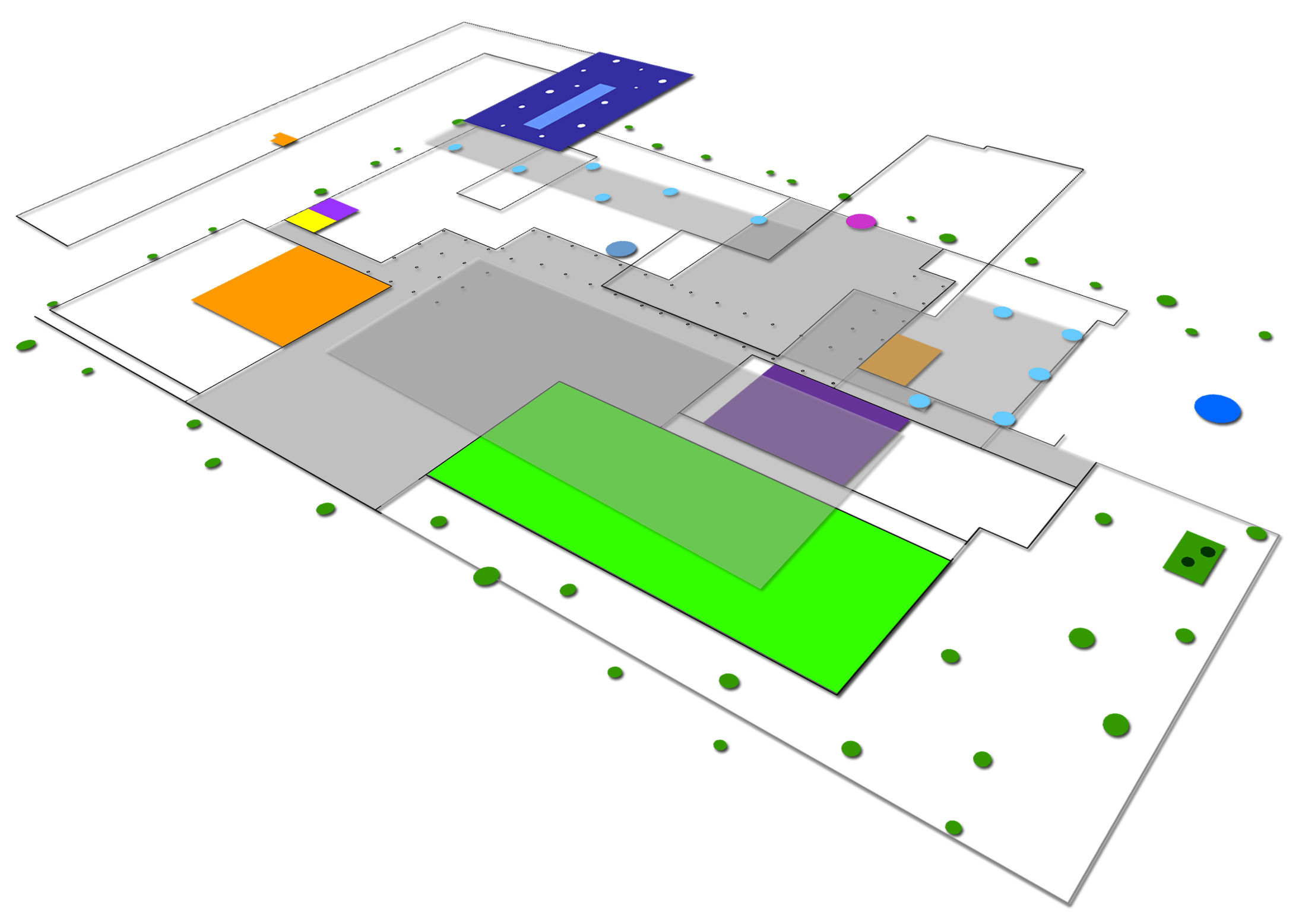

We chose to experiment with the technique in two diverted forms: ice coring and the making of strata from materials collected around the high school. Preparation of strata. The study of archaeological furniture, which was no longer only stratigraphic but also planimetric, led to work focusing on the collection of information on the school’ s premises.

In fact, the pupils, in teams, collected elements or clues in sectors identified on the expanded plans of the school that would allow them to reconstruct what is known in archaeology as material culture.

Thus, since we could neither search the building nor its surroundings, we assumed that we would apply this spatial approach in part by collecting traces of activities within the building, materialized by the objects used or abandoned in the buildings and yard, considered archaeological objects that will be studied using the same processes.

These objects, mainly materialized by rubbish in the courtyard, but also objects of daily life, especially in dormitories, bathrooms, or kitchens, make it possible to identify the culture of the populations who live in these places, which are also identified with regard to their function. We help the pupils to identify traces of their own activity, for example lost and sometimes anachronistic objects such as socks hidden not in cupboards but under beds, or eating habits through the presence of sachets of condiments in the boarding school kitchen.

These surveys or wanderings have made it possible to collect a set of elements, each of which, located and listed, has been photographed, drawn and determined. Then, each group presented its collection, placing the objects in context with the association of the plan and photographs that had been taken with the iPads during the school surveys.

The hypotheses put forward during this presentation of the sets, placed in their contexts on the enlargement of the establishment’s plans, were then the subject of interpretative texts.

In this action, the students, who were truly archaeologists, perceived the subjectivity of a reality that was nevertheless theirs. For example, the discovery of two fragments of a love letter, located in different places, has been the subject of many questions. If some of them knew the addressee, why was this object in the courtyard, why was it not in the possession of its owner, what had happened? Another story was born.

In the 1960s, the study of the Magdalenian site of Pincevent conducted by André Leroi-Gourhan oriented the methodology towards this approach to archaeological furniture by developing spatial analysis based on the distribution of lithic artifacts. This truly founding study made it possible to restore both the activity and the location of the camp’s activity areas. The impact of this research has extended to all types of furniture, including pottery. However, it must be admitted that this approach, while disrupting the archaeologists’ excavation habits, involved many constraints, including the recording and rating of archaeological data.)

In the same perspective, the pupils of the Pierre Emmanuel high school perceived that the objects could speak in their context, but could also be positioned in an anachronistic way. In this sense, it appears that even the closest reality can be subjective.

During the second production session, we examined the objects that had been discovered and listed, and made hypotheses based on the location of each of them. This study resulted in the writing of texts that correspond to the formulation of hypotheses but also to interpretations that go beyond the school context. Thus, we no longer talk about facts, but we tell a story, for example, about the possibility of a sock being lost by a murder victim.

Ice core drilling

Like archaeologists specialising in applied sciences, the techniques have been experimented and tested several times. The completed productions were photographed, quickly before they were cast, or projected onto the facades of the buildings surrounding the high school.

In fact, it is through the stratigraphic approach of the archaeological layers that the different phases of occupation of an archaeological site are determined. The stratigraphy of a site therefore constitutes its vertical, and therefore underground, memory. This superposition of sedimentary layers is obtained through excavation, but also by coring, particularly in underwater environments or during archaeological diagnoses over large areas.

The notion of subjectivity which seems to be during this process, in addition to highlighting the first flaw in archaeology, and is the limit of it, is nevertheless the first parameter of the creative process which has liberated the imagination. Thus, the inhabitants of the site reconstruct their own reality.

At a time when major preventive excavation projects are being carried out, giving rise to vast territorial studies, where time and resources seem to be limited, it seems that the definition of precise and above all “optimal” methods is more than ever a major element of research in the humanity and social sciences as a whole. Indeed, the search for a scientific approach makes it possible to reduce the share of subjectivity and thus to make hypotheses that are difficult to prove.

Despite the omnipresent and necessary contribution of the exact sciences, which provide more precise information. It is a cruel dilemma to choose the information and the amount of data to be processed. Many unexplored data will remain unknown because of the need to make choices.

To better understand this state of affairs, it is necessary to refer to the research carried out since the 1970s and 1980s in the context of “New Archeology,” for Anglo-Saxon countries, and the simultaneous development of these environmental and territorial approaches, including A. Leroi-Gourhan was the forerunner. The contribution of the so-called exact sciences seemed to give the idea of a more precise approach to archaeological discoveries, especially in Prehistory, a period not documented in the texts. Thus, the development of dating techniques has given a new impetus to research in prehistoric archaeology, which was quickly taken up in the 1980s in the field of historical periods, even for the most contemporary periods, for example mining and industrial archaeology.

This fundamental study of the relationship between man and his environment leads to a real reflection followed by the creation of new research tools, in particular the computer tool currently generalized to all social and human sciences research, but also the mathematical tool for the definition of micro or macro cultural, social and technical structures. This set of tools is generally integrated into an interdisciplinary research programme in which the natural sciences and related disciplines (Anthropology, Geology, Physics) have a major role to play.)

As with any archaeological study, it is necessary to make assumptions, which are often the subject of new research perspectives.

If we position ourselves as archaeologists, we must admit that the restitution of the high school in its occupational dimension can be compared to a real archaeological experimentation. From this perspective, the occupants, who are also the actors of the archaeological fact in their environment, were able to apprehend their actions and question them. Through their writings, they have demonstrated that memory does not allow us to accurately reproduce the facts, which are often interpreted, even if the time elapsed between the activity and its analysis is short. The hypotheses put forward speak of their creativity, and perhaps beyond, of a real appropriation of their everyday school life.

The storage of data in the archive room that takes place in the museum, allows future high school pupils, in 10, 20, or 30 years the temporal approach that was initially considered by the technical experiment. In this sense, this experience seems to be the beginning of a real archaeological investigation.

Laurence Cornet